For denizens of the borderlands, surveillance is a constant presence. In the last two decades, as the budget for U.S. Customs and Border Protection has tripled to nearly $20 billion, communities have increasingly found themselves monitored by portable radar systems, ground sensors, fixed and mobile surveillance towers, and other technologies.

In June 2022, Nogales, Arizona residents watched as CBP installed a 15,000-pound weight a mile and a half north of the U.S.-Mexico border. Tied to it was a 70-foot-long helium blimp. Known as a Tethered Aerostat Radar System—or Aerostat—the unmanned balloon was equipped with cameras that would operate day and night, providing constant, low-level surveillance of the city and its surroundings. CBP installed the massive surveillance balloon over residential neighborhoods without consulting with or notifying residents.

Nogales’s Aerostat was far from the first one launched over the borderlands, but its technology was more invasive. Arizona’s first Aerostat, at Fort Huachuca, was installed in 1988, according to documents in the University of Arizona Library’s Special Collections. It was soon followed by blimps in Yuma and Deming, New Mexico. By 2022, CBP operated balloons at those locations as well as in Marfa, Texas; Puerto Rico, off Texas’s South Padre Island; and at seven points in Texas’s Rio Grande Valley. But whereas some of the older blimps—including the one at Fort Huachuca—were limited to radar, the Nogales system was designed for video surveillance.

Residents of Nogales saw the Aerostat—constant, visible, and enormous—as a step too far. The blimp seemed different from the surveillance towers and other ground-level technologies. As Santa Cruz County sheriff David Hathaway put it in a Border Chronicle podcast, some residents thought of it as a “spy blimp.” Its presence was uncomfortable because it massively expanded authorities’ vision on the border.

The militarization of border communities including the installation of walls, surveillance towers and floating “spy” blimps has increased exponentially since 9/11. For more than two decades, David Taylor a professor of art at the University of Arizona, has been documenting the shifting borderlands. For his most well-known project, Monuments, he spent seven years photographing the 276 stone obelisks that mark the U.S. and Mexico’s land border, which stretches nearly 700 miles from the Pacific Ocean to El Paso, where the Rio Grande begins to mark the international line. In DeLIMITations, Taylor collaborated with Tijuana artist Marcos Ramírez ERRE to install replicas of these obelisks along the 1821 U.S.-Mexico border, which ran from southern Oregon through Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, and Texas. That line, delineated by the Adams-Onís Treaty, was never demarcated on the ground.

His most recent exhibit, COMPLEX, which was on view from October to December 2024 at Pidgin Palace Arts, in Tucson, Arizona, invited viewers to watch the watchers. The show combined works from three of the artist’s recent series: Panorama/Panopticon, Ambos Nogales; Prototype Structures for the Triumphal Architecture of Manifest Destiny; and the series that gave the show its name, COMPLEX.

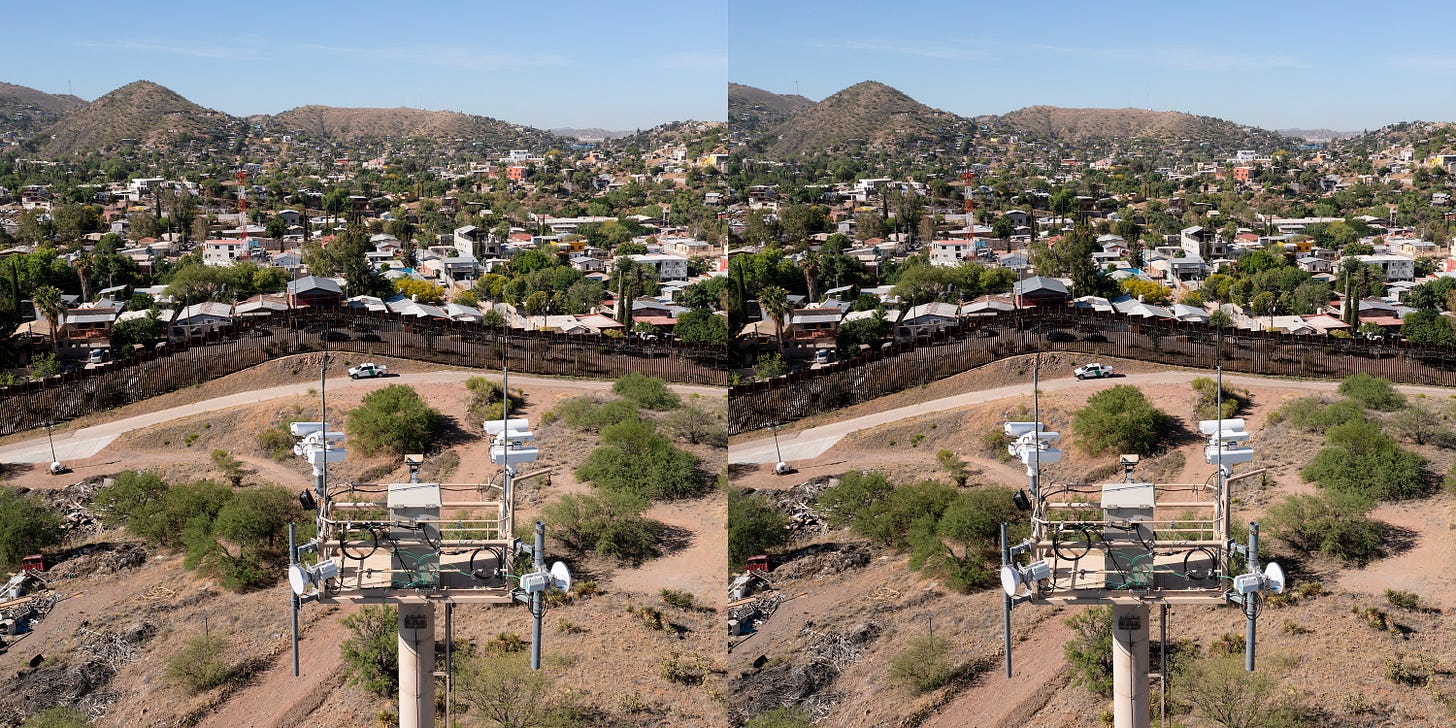

In Panorama/Panopticon, Ambos Nogales, from 2024, two aluminum stereoscopes are mounted on tripods. A stereoscope, a device invented in the 1800s, creates 3D images by manipulating the depth perception of its two lenses; the so-called stereoscopic images you insert into them show the same image twice, side by side. Lining one wall of the gallery was a shelf of these doubled photographs. Most showed camera towers from around Nogales, Arizona, as they peered over the border wall and into the ordinary neighborhoods of Nogales, Sonora.

Looking at the camera towers through the stereoscopes meant using an old technology to perceive a contemporary one. Oddly, as you pressed your eye to the metal eyepieces, the surveillance towers, too, seemed outdated. As personal technologies like laptops and smartphones have become ever sleeker, wires, antennae, and other odds and ends have come to look obsolete. On the other end of the old-fashioned spectrum, the tower’s crow’s nest of sensors, scanners, and other bobbles seemed unwieldy and droll.

Across the room was another piece from 2024, titled Prototype Structures for the Triumphal Architecture of Manifest Destiny: a gray model of the steel-bollard border wall, fabricated using a 3D printer, sitting atop a plywood base on the gallery floor. At double its height stood a camera tower supporting the fence line. Next to the model, on the wall, three television screens played video loops: one showed Border Patrol trucks at a campsite along a gap in the border wall; another, seemingly in the riverine landscape of the Rio Grande, showed agents putting migrants into single-file lines alongside an unmarked bus, their personal belongings in a pile to the side, as though to be left behind; a third showed a line of people in orange jumpsuits moving through the barren landscape of a detention center.

Directing viewers’ gaze downward, the videos allowed visitors to become the model’s camera, high above the wall. The viewers could thus see through the camera instead of looking at it using the stereoscope; as a result, the tower was no longer arcane but creepy. It—and now the exhibit’s visitors—were spies, overlooking dozens of migrants and asylum seekers on their way to one of the border region’s many detention centers.

COMPLEX, whose photographs were taken from 2019 to 2023, engages with this so-called American gulag—the hundreds of immigration detention centers and other carceral facilities hidden around the borderlands. Since 1994, the number of immigrants detained each day has increased tenfold, thanks to policies that require detention for more reasons and for longer periods. Those policy changes have largely benefited private for-profit companies like the GEO Group and CoreCivic, which operate many of the facilities.

Taylor captured this “vast industrial landscape [of] nondescript facilities” using a drone. On the gallery wall, he arranged a grid of 32 of the aerial images, which spanned California, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. With its nimble and exhaustive access to deeply hidden places, COMPLEX took viewers from the fixed tower camera of Prototype Structures into an Aerostat, an all-seeing “eye in the sky” that can take in its surroundings from a knowing distance.

And what did that omniscient perspective show? Mirroring Taylor’s geographic movement from east to west, as the photos shifted from left to right in their grid, their landscapes change from brown to green—from desert to farmland to forest. In Calexico, California, the floodlights illuminating the road looked like a fiery moat. In Chaparral, New Mexico, the rising sun reflected off the facility’s windowless metal walls. In Laredo, Texas, the Rio Grande cut diagonally across the left side of the image. The layout of the detention centers was repetitive: a rectangle of industrial-looking buildings protected by a ring road of straightaways with rounded corners. Changing slightly with the angle of each drone shot in the grid of photos, the structures started to look like a single shape rotating through space.

While the jails’ geometry made the grid magnetic, there was little beauty to find in the structures themselves. In a 2023 Border Chronicle podcast, Taylor refers to detention centers as the “most significant architectural legacy we have created in the last 20 years.” The cheaply constructed buildings, seemingly more suitable for storage than habitation, are relentlessly mundane. They are designed for invisibility, so that what happens within them goes unnoticed.

Perhaps most emblematic of how the evisceration of ethics and aesthetics go hand in hand was an image kept separate from the rest. The image, taken not at an angle but looking straight down at the ground, showed two lines of rectangular structures made of concrete. Seen out of context, they could easily be confused for a work of modernist land art, like Donald Judd’s concrete boxes. But the image’s concrete boxes were utilitarian: they were prefabricated detention cells located in Eloy, Arizona, 50 miles northwest of Tucson. If civic values are reflected in architecture, the legacy of the 21st-century United States is stark and inhumane.

In Nogales, the Aerostat didn’t last long. After an outcry from residents and Sheriff Hathaway, it was grounded. Its presence made too obvious the fact that everyone in the borderlands is being watched. In a February 2023 podcast, Sheriff Hathaway told the Border Chronicle, “You could see it right out the window of my office … anchored right there and potentially looking right in the window.” Some constituents who could see if from their house, he added, were even afraid to shower with it looming overhead.

It was not the first time that the Department of Homeland Security capitulated to southern Arizona communities. Owing to residents’ protests and organizing, the Tucson sector remains the only Border Patrol sector in the Southwest without permanent interior checkpoints. In fighting back against intrusions to their privacy, borderlands residents have made it clear that they are surveilling the surveillants. Their watchfulness works—even when they use less advanced technologies than those at the government’s disposal. The naked eye and the conscience, it seems, can go a long way.

Recently, President Trump reversed a Biden administration policy to phase out detention center contracts with private prison companies—a step toward better regulating and overseeing the conditions inside facilities like those captured in COMPLEX. Stock prices for private prison companies have spiked, and companies like CoreCivic, which donated $500,000 to Trump’s inauguration, are expecting to profit. Finding ways to keep watch on border surveillance, militarization, and the treatment of those held in detention centers will now become more important than ever. COMPLEX offers its viewers a map for continued vigilance. For those who take up the mantle, it’s a matter of—as Taylor refers to his projects—“endurance work.”

Read more: Read More

Read more: Read More