Ismael Limón is an ejidatario, or a member of a ranching collective, in Molino de Camou, Sonora, a town on the banks of the Río Sonora northeast of the city of Hermosillo. “We are small cattle raisers, with between five and 15 cows,” he said.

Just above Molino de Camou sits a dam called El Molinito. Since the dam began supplying water to Hermosillo via an aqueduct called the Acueducto El Molinito, Limón said, he and other ejidatarios have struggled to receive the water they’re entitled to.

“When the aqueduct was built in 2008,” Limón explained, “there was an environmental impact statement and an agreement establishing its rules of operation—that it could only operate from May to September, only with a certain flow, and it had to respect the rights of the [ejido] users. They haven’t complied with any of those three points.” Instead, despite their registered senior water right, “we constantly fight to be able to irrigate,” he said.

Now federal and state officials in Mexico have announced a plan to construct three additional dams upstream of El Molinito. According to the country’s National Water Commission, CONAGUA, construction will begin in July, but there has been no required community consultation, environmental impact statement, or cost-benefit analysis. Experts and affected community members alike are organizing to demand that the government rectify its omissions—and consider alternatives to the new dams.

Historically, the Río Sonora ran 250 miles, from the mountains of Cananea—a copper-mining city 25 miles south of the U.S.-Mexico border—to the Gulf of California. But the river has not reached that historic outlet since 1948, when the Abelardo L. Rodríguez dam was constructed adjacent to Hermosillo. Instead, it runs dry at the capital.

In the 1970s and 1980s, heavy rains caused the Abelardo L. Rodríguez dam to overflow. In 1991 the state of Sonora built the El Molinito Dam about 17 miles upstream of the city—and just above Limón’s ranching community. Though it was initially created as an emergency overflow dam, it was reclassified as storage for the city’s water supply when the aqueduct to Hermosillo was built. The downstream Abelardo L. Rodríguez reservoir is now dry because there is too little water to fill both dams.

In 2023, Sonora’s state water commission announced plans to build two new dams as part of the state’s 2023–53 hydrologic plan. The agency said it would sell most of the dry bed of the Abelardo L. Rodríguez reservoir to raise funds for the new structures, which would provide water for Hermosillo.

One of the people confused and surprised by the proposal was Rolando Díaz-Caravantes, a geographer and professor at the Colegio de Sonora’s Center for Studies of Health and Society. Díaz-Caravantes had been studying the impacts of the El Molinito Dam on nearby communities like Limón’s. Using Landsat imagery—satellite photography that captures changes in landscape over time—he determined that from 1993 to 2011, lack of water had led to a two-thirds decline in agricultural land use in the communities surrounding the dam—pointing to serious livelihood concerns. Though the agricultural land was replaced by some mesquite forest and riparian vegetation, the overall amount of vegetation in the area had declined by about half.

After the announcement of the state hydrologic plan, Díaz-Caravantes presented his findings at a public forum, saying the new dams were likely to have similar effects. He invited Limón and other affected ejidatarios to share their firsthand experiences. “We’re already living through what those communities are going to experience,” said Limón.

Instead of being halted, however, the dam-building plan was expanded. On November 21, 2024, President Claudia Sheinbaum announced in her morning press conference that the country’s National Hydraulic Plan would include not two but three dams in Sonora—in Sinoquipe, on the Río Sonora, and in Puerta del Sol and Las Chivas on the Río San Miguel, a tributary. The government anticipated allocating over 7 billion pesos—$350 million—in federal funds for the construction.

Sonorans concerned about the plan began to organize. The Movement in Defense of Water, Territory, and Life in Sonora began meeting weekly at a rental hall in central Hermosillo. Along with Limón and other ejidatarios, attendees include university professors, members of anti-capitalist and feminist movements, a graphic designer, and a social worker. They strategize about how to communicate their opposition to the dams to both the country’s leaders and the general public.

The group petitioned the federal government for a meeting, but when this went unanswered, members approached Sheinbaum at a highway inauguration. Several managed to speak directly with Sheinbaum as her car arrived and presented her with a letter requesting a meeting, while others unfurled a banner that read “Solicitamos diálogo”—we are asking for a conversation. In another action two weeks later, about 40 cars formed a caravan, driving from the outskirts of Hermosillo to city hall, where they held a demonstration with banners, signs, and speakers.

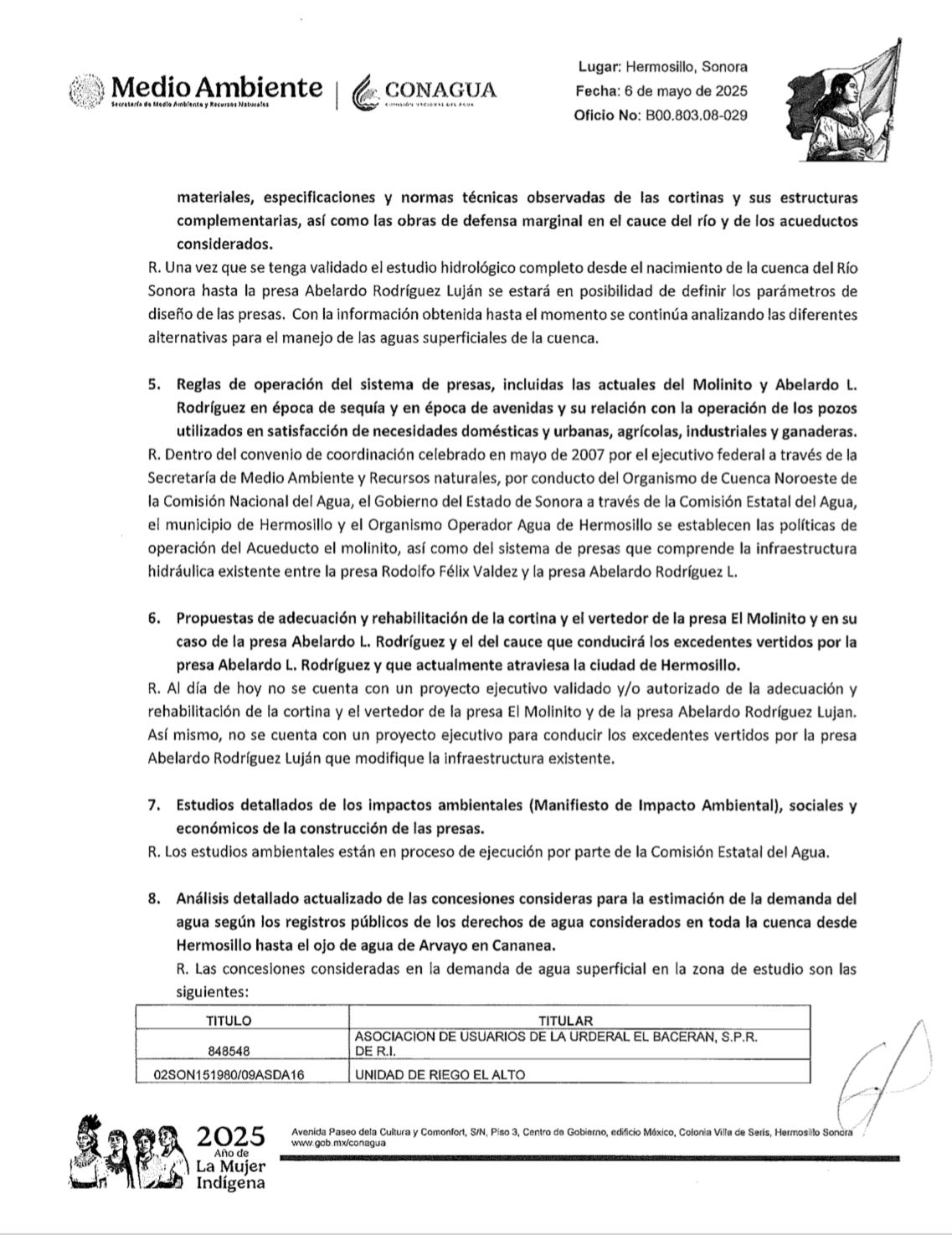

Meanwhile, a group of specialists, including Díaz-Caravantes, worked through bureaucratic channels. At the end of February, the group sent a letter to the president, the governor of Sonora, and the secretary of natural resources and environment requesting the results of 12 required studies, including hydrologic and climatological studies showing that there is enough water flowing in the river to justify the dams; cost-benefit analyses that consider alternatives to dam building; structural plans showing the dams’ location, materials, and capacities; and environmental impact studies. “There’s no water,” said Díaz-Caravantes. “What good are three empty dams?”

On May 6, the Secretariat of Natural Resources and CONAGUA sent a reply. The hydrologic study, they said, was still in process, and only once it was finalized would it be possible to develop the dams’ design. The environmental impact studies, the letter noted, were also “in process.”

By the time that reply arrived, however, CONAGUA had announced that construction on the dams would begin in July. “This alarmed us as specialists,” Díaz-Caravantes said, “because we see that there are no plans, no impact studies, no cost-benefit analysis, no consultation with the river’s communities.” Residents of the town of Ures, near the proposed Puerta del Sol dam, had begun to see surveying equipment, and some complained of intrusion on their lands.

“It’s pretty bold of them to announce that construction is going to begin in July when the studies aren’t even available,” said biologist Lara Cornejo, another member of the group.

Some speculate that there are ulterior motives behind the authorities’ insistence on building dams. Sonora governor Alfonso Durazo, for example, may stand to gain from the plan. In 1994, Durazo bought 250 acres of the Abelardo L. Rodríguez reservoir’s bottomlands, so if the reservoir area is sold, he could be among the beneficiaries. Additionally, there are several mines near the proposed Sinoquipe dam site, leading some to believe that the water stored there will mainly benefit extraction companies.

Instead of dams, the proposal’s opponents say, officials should address Hermosillo’s water needs by remedying deficiencies in the city’s water system. According to Agua de Hermosillo, the city’s water utility, 50 percent of the water that enters the city’s distribution infrastructure is lost to leaks. (In the U.S., the national average is 14 percent.)

“For years, the countryside has been providing water to the city,” said Limón. “They bought from farmers along the coast, and it didn’t solve the problem. El Molinito didn’t solve it. Then the Acueducto Independencia—that didn’t solve it either. They’ve brought water from sources all over, but they’ve never repaired the leaks in the water infrastructure. You’re not going to solve the problem by bringing water to a bottomless barrel.”

Read more: Read More

Read more: Read More