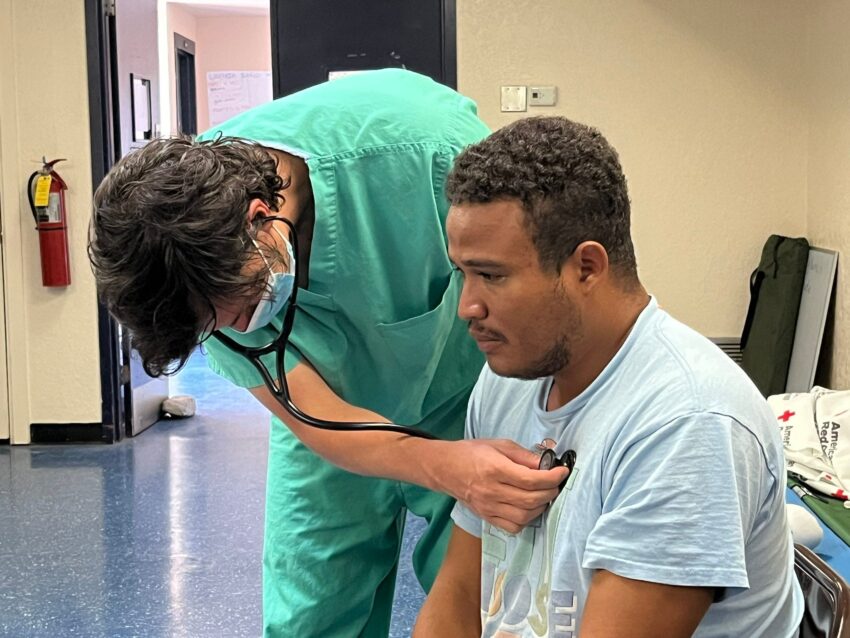

We are happy to announce that we will be doing occasional guest op-eds here at The Border Chronicle, and today is our first. You probably remember Brian Elmore, the emergency-medicine resident physician who did a Q&A with Melissa last month. In this op-ed he vividly describes what border deterrence does to a person’s flesh, and he makes an eloquent call for its end. After 30 years of this strategy, which has proved both deadly and harmful for people crossing the border, it is our honor to publish this reckoning and call for action, especially since we are entering an election year (it is now November, after all).

Brian is also the cofounder of Clínica Hope, a free clinic for migrants in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, which he runs with the nonprofit Hope Border Institute.

And lastly, !Feliz Día de Muertos! Todd

The Political Pathology of Border Deterrence: An Up-Close View of How This Policy Looks in the Emergency Room

“Deterrence won’t solve migration—it will only maim and mangle more men, women, and children. It will send more people to my emergency room. Some it will send to the morgue.”

My face was inches from his flesh as I pierced it with my needle. A tiny drop of blood emerged from my pinprick and fell to the floor. Suturing wounds can be an intimate procedure; you draw the pieces of flesh together as if it were a puzzle. You try to approximate the flesh edges as best as you can, rewinding time to close the wound.

The patient lying before me was a Venezuelan man, the father of a family whose encounter with the border had brought them to my emergency room.

As an emergency physician in El Paso, I thought I had become used to all the perverse pathologies of the border. Fractures from border-wall falls were common, exposed bone penetrating flesh. I’ve treated both hyper- and hypothermic patients, lost or left to die in the desert.

But tonight the injuries were new. The family members—two children and their parents—had arrived with widespread body lacerations. They were victims of the concertina wire newly installed by the Texas National Guard along the banks of the Rio Grande.

The family had arrived to the razor wire, drawn by rumors that officials were allowing asylum seekers to cross between ports of entry. As a crowd grew behind them, the family was crushed between the wire and an increasingly agitated crowd. “There was only one way to go,” the father said. “Under the wire.”

The smallest child had escaped injury, but another child, a girl who looked to be 10 years old, had not. I repaired her lacerations first. It was jarring, treating a child whose injuries were deliberately inflicted by my state government. The barbed wire had performed the job intended by Governor Abbott—to maim and mangle the flesh of migrant families. She was stoic as I pieced together her skin.

The father, whose attention I turned to next, shed silent tears as I sewed shut his wounds.

As I worked, I made small talk to keep his mind occupied. I began to go through all the questions needed for my medical documentation. When I got to surgical history, he lifted his shirt to reveal a thick scar snaking its way along the left side of his chest. I was stunned. It was a thoracotomy scar—a traumatic procedure that is usually a Hail Mary, last-ditch maneuver when the patient is as good as dead and all else has failed.

“I was stabbed in the chest by a thief in Caracas,” he said, staring at the ceiling. In the thoracotomy that followed, his flesh would have been cut down to the bone and his ribs spread. His lungs would have been pushed aside and the pericardium, the fibrous sack that envelops the heart, cut to reveal the heart. Any damage the knife had done would be repaired.

This procedure is rare because it is usually unsuccessful. This was the second thoracotomy scar I had seen on a living patient—both of them Venezuelan migrants, victims of violence in their home country.

The thick and thready scar snaking its way over my patient’s chest was a testament to the constant threat of violence in Venezuela. In the absence of war or conflict, it can be difficult for Americans to comprehend the hopelessness that many now feel in Venezuelan society. But the hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans uprooting their families to make the dangerous trek through the jungles of the Darien Gap and cartel-dominated Mexico vividly demonstrated the desperation.

“Venezuela is so ugly right now. I want them to go to school. I want them to succeed. I want to work. I want to be able to provide for my family,” he said.

I wiped away some blood with cotton gauze. “How was the journey? Did you cross the Darien?”

“Yes,” he said quietly, almost a whisper. “It took us three days. We saw five dead bodies. Somebody in our group died. We think he had a heart attack. His body is still there in the mud.”

Mexico was worse than the Darien, he said. “The police beat us and demanded money from us. The cartels did the same. I was kidnapped. The government doesn’t help you. They don’t care about you.”

The barbed wire that maimed this family was only the newest weapon in a strategy of deterrence—a strategy that has been decades in the making—the federal government’s attempt to discourage migrants and asylum seekers from crossing the border by making it as dangerous and deadly as possible. Under Governor Abbott, Texas has embraced and expanded deterrence to macabre ends. As part of Operation Lone Star, Texas has strung miles of razor wire along the border, placed floating buoys in the Rio Grande separated by saw blades, and deployed thousands of National Guard troops.

The family before me was yet another testament that a policy of deterrence will never work and will only cause more pain and suffering. Deterrence fails to recognize the desperation of these families that drives them to seek safety in our country. It fails to recognize the crucible of their journey to the border. By the time most Venezuelan asylum seekers have reached our southern border, they will have braved the jungles of the Darien Gap and encountered corrupt security officials and sadistic cartel members in Mexico. Barbed wire and a wall is not going to stop any of these migrants, who have survived the journey to our border.

The harsh and sterile policies of deterrence also fail to recognize these pilgrims’ most important motivation: love. This family’s love for each other is the potent force that overcame deterrence. Love for their children, a desire to give them the safe life that they deserve, was ultimately what drove this family to embark on their odyssey.

Deterrence won’t solve migration—it will only maim and mangle more men, women, and children. It will send more people to my emergency room. Some it will send to the morgue.

I’ve come to start calling the characteristic injuries of the border “political pathologies.” These patients require medical treatment in my emergency department because our policymakers have consciously decided to make the border as deadly and dangerous as possible to cross. If the pathologies are political, then the solution is too.

We must replace deterrence with a humane immigration system that respects the dignity and inherent worth of all people who would seek refuge and opportunity in this country. Any proposed solution to the problem must also address the root causes—violence, corruption, poverty, the changing climate—that force a people to flee the land of their birth, a painful uprooting that few people would willingly choose.

I smiled at my patient as I applied a dressing to his sutured wound. “Welcome to America,” I said. My patient’s scar, threading its way across his chest, echoed the scar that the border wall has made on our landscape.

I had to go. There was another border-wall fall patient to see.

Read more: Read More