Broken satellites lie in junk heaps alongside refrigerators and mattresses. Libraries have been shuttered and books banned. A changing climate has pushed the electricity grid to the brink. Newspapers are dead; information comes only through specific controlled portals. Deportation flights sound overhead.

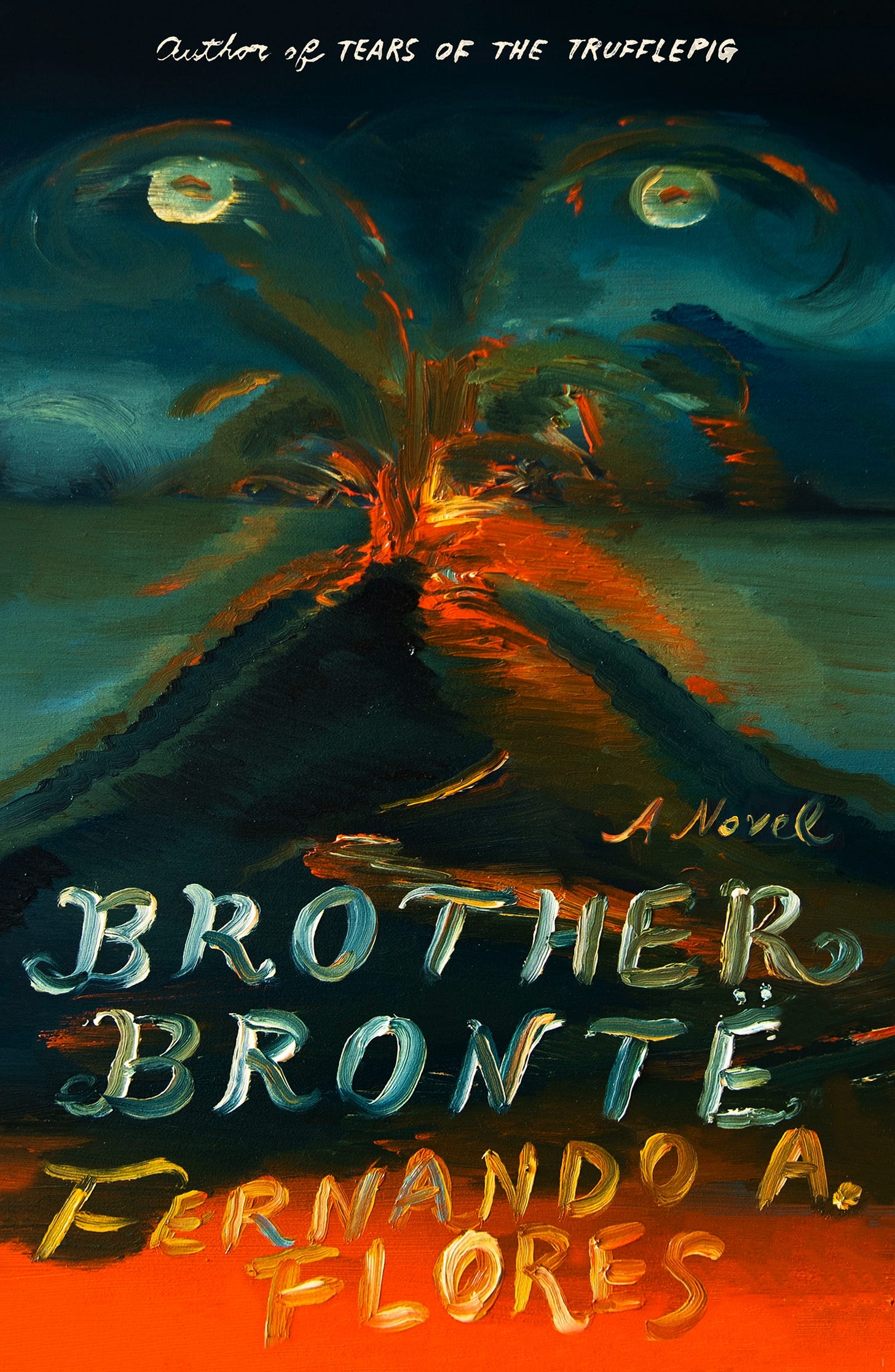

Familiar as it may sound, this isn’t a description of Elon Musk’s America. It is Pablo Henry Crick’s Texas. In Fernando A. Flores’s new novel, Brother Brontë, Crick is the mayor of Three Rivers, a city once privatized in the service of big tech companies, whose residents now scrape by in a heavily policed mess of crumbling highways and rundown homes.

Flores’s work came into my hands at a moment when I had decided that the borderlands evaded literature. The problem, as I had diagnosed it, was that the novel is a personal form, while the border is a societal phenomenon; no character could do justice to the structural forces that loom over the region.

Then I found Flores’s 2022 short story collection, Valleyesque. Its deadpan narrations of a world just a few degrees off-kilter felt like a version of George Saunders’s Pastoralia set in the very specific terrain of South Texas. In one three-page story, possums write best-selling tell-alls and plot to take political control of the Rio Grande Valley; in another, the composer Frédéric Chopin lives in Ciudad Juárez, and his piano has been detained in customs. The stories made me laugh, but I couldn’t figure out what to make of them.

Then everything I encountered started to feel like a Fernando A. Flores story. The southern New Mexico town that’s on the map but turns out to be an abandoned house taken over by owls? Flores probably thought of it first. The time I got stopped at a checkpoint only for the official to spend five minutes using my lint roller to suction dog hair off her uniform? Valleyesque. The widows of two rival cartel bosses who now share a house in one of the fundamentalist colonies in Chihuahua? Steal this idea, Fernando, please.

While Flores’s work traffics in absurdity, I gradually realized, its humor is tangled with a deep earnestness. Across his books, his characters confront corruption and find meaning through literature and music, even as their lives are indelibly marked by inequality, poverty, racialization, and militarization.

For instance, in a short story from Flores’s first book, Death to the Bullshit Artists of South Texas (2018), a character named Beebee Kwaiczar grows up as a migrant farmworker before going on to tour the world as an experimental musician. He retires to a hermetic life in the Rio Grande Valley, keeping 25 rat terriers for company and listening to Stravinsky, grateful for the calm while recognizing that the land carries a “deep darkness.”

Then he begins receiving notices that a border wall will be built through his property. Before he leaves, he and his daughter organize a music festival at the site—featuring a paintball rink, tarot readings, and a pop-up coffee shop run by single mothers. “For the first time since his youth Beebee felt that he was floating in outer space,” writes Flores. But then the utopian dream abruptly ends—he can’t stop the wall.

The 2019 novel Tears of the Trufflepig turns up the volume on this border-militarization theme. The book’s Rio Grande Valley setting is not the slightly fabulist take on reality of Death to the Bullshit Artists, but a near future in which a militia called the Border Protectors patrols two border walls with tanks, no one has seen a live bird in years, and there’s a black market for the shrunken heads of members of the Aranaña tribe. Drugs have been legalized, so “syndicates” have diversified into kidnapping scientists to work in laboratories reviving extinct animals for illicit fine dining.

The novel’s protagonist, Esteban Bellacosa—whose surname both resembles the word bellicose in English and means “beautiful thing” in Spanish—is a working-class Mexican American tenderly drawn by Flores with the double consciousness of a borderlander. Like the punk bands of Death to the Bullshit Artists, Bellacosa dreams of a quiet life—but that dream remains out of reach.

When he chances upon the destruction of land that a colleague once envisioned making “functional again and selling naturally grown onions,” Bellacosa begins a fight to bring the dream closer to reality. He goes on an improbable quest to uncover a conspiracy between syndicates, the valley’s white elite, and the Border Protectors—who are together responsible for environmental destruction, organized crime, and anti-Indigenous violence. Another character knights him as a searcher of justice: one of “the people who face the world, and not simply for the challenge or to prove a point [but] to expose the corruption hindering our collective spirit in its continual ascent.”

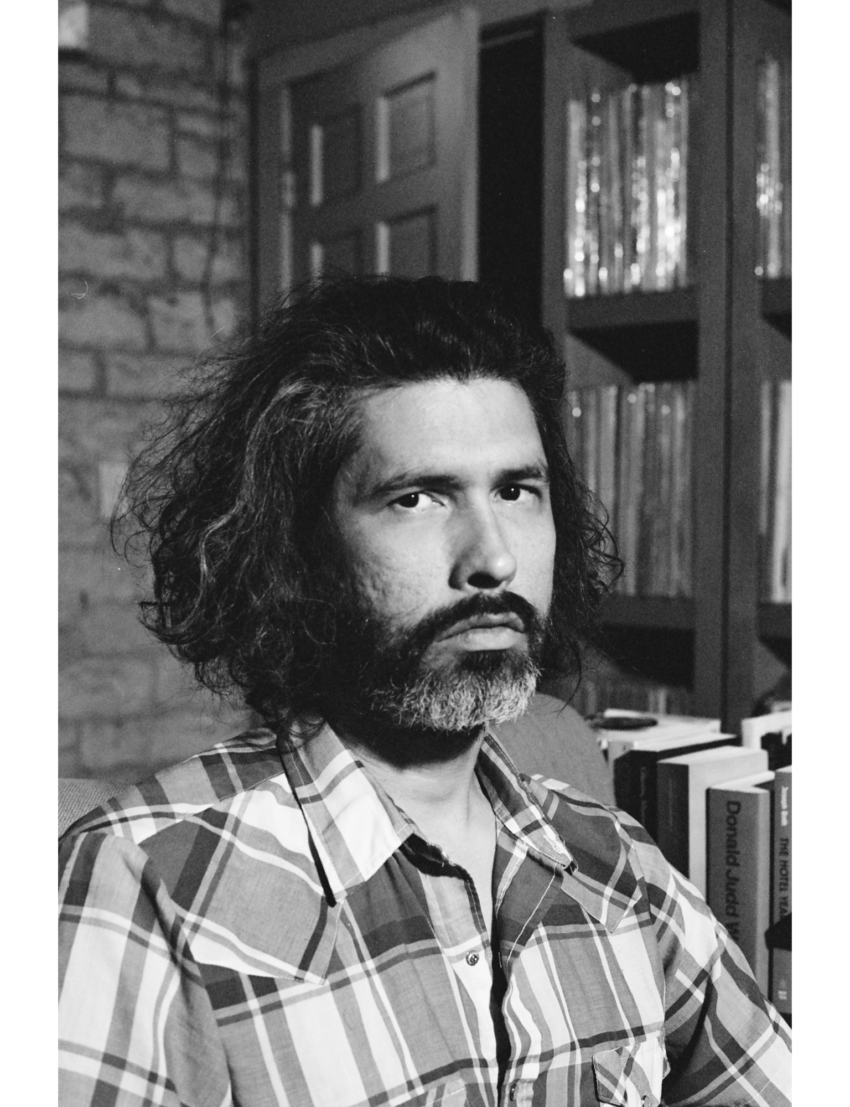

Flores’s latest work, Brother Brontë, also takes on the forces that corrupt people’s attempts to live a good life. Released on February 11, the novel features a cover by Na Jin that evokes Mexican painter Dr. Atl’s Erupción del Paricutín (1943) watched over by The Great Gatsby’s Celestial Eyes. Whereas Flores’s previous books take place in the Rio Grande Valley, Brother Brontë is a central Texas novel in everything from its trees to its freeways. It shows that all of Texas is part of the borderlands.

The story is divided into three parts. The first introduces readers to the characters Neftalí and Prosperina, friends and former bandmates eking out survival in Three Rivers. It follows them around the decaying city, exploring its people and places.

They visit their former band’s bassist, Alexei, who is swept up in inventing a new currency that will ingratiate him with Crick, the evil mayor; they go to the fish cannery that doubles as a forced-labor camp to visit Bettina, who became Neftalí’s adoptive mother after the death of her activist birth mother. Bettina and Neftalí are among the city’s final literate citizens, and they secretly share the few books they can find—including one by Neftalí’s favorite author, Jazzmin Monelle Rivas, titled Brother Brontë.

The second section of Flores’s Brother Brontë tells the story of Rivas’s literary career up to the writing of her Brother Brontë—a trajectory that perhaps resembles Flores’s own: she works in the service industry and writes experimental fiction on the side; though she struggles to sell her first novella, she finds success when an editor who published one of her stories lands her own publishing imprint and offers her a two-book deal. Then, watching television while far from Texas, Rivas sees footage of Neftalí’s mother fighting the privatization of Three Rivers. “Look at all the chaos they’ve created for the poor people who live there,” she comments. “And they’re blaming it on this activist, Angélica, who has been organizing against the tech companies all along.” Soon thereafter, she writes Brother Brontë—the novel that ends up being “quite possibly the last intact novel in Three Rivers.”

Rivas’s Brother Brontë is a story of people slowly realizing that they have been lied to. In the third section of Flores’s Brother Brontë, Neftalí reads Rivas’s Brother Brontë repeatedly while also being lied to. Through its “newscubes,” Three Rivers’s government controls the information that reaches its residents. It blames the city’s constant darkness on volcanic eruptions in Mexico, though some suspect explosions are responsible, and it tells residents that they no longer need to wear N95 masks because the ashy air poses no health hazard.

Then a long-lost friend of the characters—who lives on a farm in George West, a nearby town that escaped Three Rivers’ privatization and austerity measures—decides to assassinate Crick. With the advantages of clean air and fresh vegetables, she can see the situation more clearly than those inside the city, and can act. The other characters evacuate to George West and join her on the farm.

At the novel’s close, Neftalí and a child whom she has taught to read animatedly enact a scene from Brother Brontë that involves waving an axe. Without consciously realizing it, they are also reenacting Crick’s murder. As members of the privileged few who can read, they have metabolized Rivas’s novel, enacted it, and saved themselves in the process. Reading nourished them in ways they can’t express.

In Flores’s prose, it’s clear that his apprenticeship as a writer likewise came from voracious reading. The story of Beebee Kwaiczar swallows up a reference to Chicano writer Tomás Rivera. Flores’s unusual use of adjectives—“boxcar fog” and “tarantula darkness”—recall Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo. Bellacosa’s unorthodox hero’s journey echoes Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49, while Brother Brontë is rich with stains of Mikhail Bulgakov.

Across his books, Flores’s characters are just as effortlessly erudite as he is, always recognizing classical compositions and becoming obsessed with little-known authors. Neftalí has visions of Mexican composer Juventino Rosas; Bellacosa has a favorite recording of Glenn Gould.

Yet Brother Brontë makes clearest that in this world, enjoying the arts is difficult. “I just need some room, y’all,” Neftalí exclaims. “I need time to go by as I sit still somewhere with nothing happening, and without worrying about dumb things like losing my books and losing my house.”

It’s difficult to find a quiet place to read in the racialized, militarized, impoverished borderlands. Flores’s novels mirror the South Texas of reality, in which nearly every county is classified as one of “persistent poverty,” in which environmental protections are side-stepped in favor of polluting industries, in which residents are six times less likely than the national average to have completed ninth grade.

The people who live with these constraints are those to whom Flores dedicates his books: the “kids,” the “exiles,” the “disappeared.” His novels are not only madcap heroes’ journeys but also testimonies to the lives unfairly limited by being born in “a time and place that … is nothing but a constant fight to merely stay afloat.” The characters dream of a world where life is not so hard. In the world they imagine, “valleyesque” would connote not the absurd and unfair but the pastoral and calm.

Brother Brontë by Fernando A. Flores (MCD/Farrar, Straus & Giroux) can be purchased from Bookshop.

Read more: Read More

Read more: Read More