This article is a collaboration between The Border Chronicle and Inkstick Media, a nonprofit newsroom focused on life amid endless conflict.

When Vice President JD Vance spoke at a security conference in Munich in February, he didn’t acknowledge that Europe and the U.S. share a similar approach to migration, one that essentially amounts to death by border. Instead, he lashed out at Washington’s European allies for, in his telling, backing Ukraine in its conflict with Russia, abandoning free speech, suppressing far-right parties, and, of course, leaving the bloc’s borders open to migration.

European leaders rushed to denounce Vance’s Munich tirade, but a week later, he doubled down while addressing the Conservative Political Action Conference in Washington DC. “The greatest threat in Europe, and I’d say the greatest threat in the U.S. until about 30 days ago,” he claimed, “is that you’ve had the leaders of the west decide that they should send millions and millions of unvetted foreign migrants into their countries.”

In the U.S., the Biden administration had already implemented restrictions last year that nearly decimated the right to even request asylum, and the Trump administration is now reportedly considering issuing a public health order that would further tighten restrictions at the southern border with Mexico. Meanwhile, the U.S. government is moving forward with a plan to carry out mass deportations and shipping people to what are effectively detention camps in foreign countries.

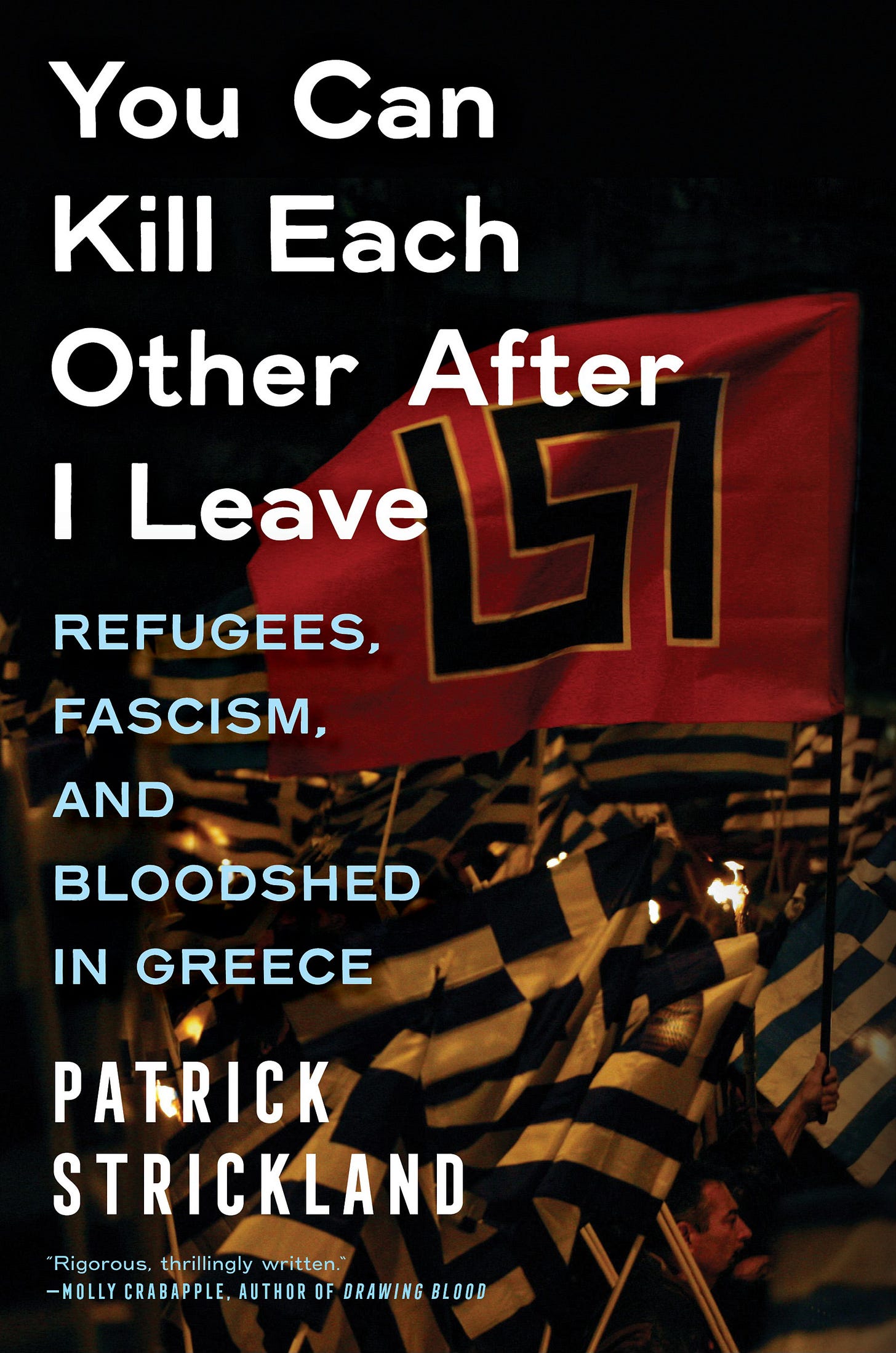

Not everyone in Europe has taken offense at Vance’s remarks. After the Munich speech, Greece’s hard right health minister, Adonis Georgiadis — known, in part, for once promoting an antisemitic book titled Jews: The Whole Truth — wrote a lengthy post on X in which he agreed with Vance’s assessment that Germany had “opened its border to every illegal immigrant” and put Europe in danger. From his prison cell, Ilias Kasidarias, a former parliamentarian with Greece’s now-banned neo-Nazi Golden Dawn party, cheered on Vance for calling out the EU “rodents” who, he claimed, had put in place “undemocratic blockades of the nationalist parties” around the bloc.

And so it went all around Europe. The leader of Romania’s far-right AUR said his party “welcome[s] the Trump administration’s vision of a free world,” while Martin Sellner, a leader in Austria’s ultra-right identitarian movement, applauded Vance’s claim that “the real enemy is within” Europe.

Vance’s speeches might have been targeted at an American audience as much they were a nod and a wink to the hardline fringes of Europe’s far right, sure, but the obvious irony is that when it comes to migration policy, much of Europe is already in lockstep with Washington.

The International Migration Organization says that in the Mediterranean Sea, which refugees and migrants often cross to reach Europe, more than 32,000 people have died or gone missing since 2014. In 1994, the United States implemented “Prevention Through Deterrence,” a policy that actively seeks to force people passing the border into more dangerous (and lethal) desert corridors and river crossings. Between 1994 and 2024, the U.S. Border Patrol recorded more than 10,000 deaths, according to Human Rights Watch, but rights groups worry that the true number could top 80,000, because many bodies are never found.

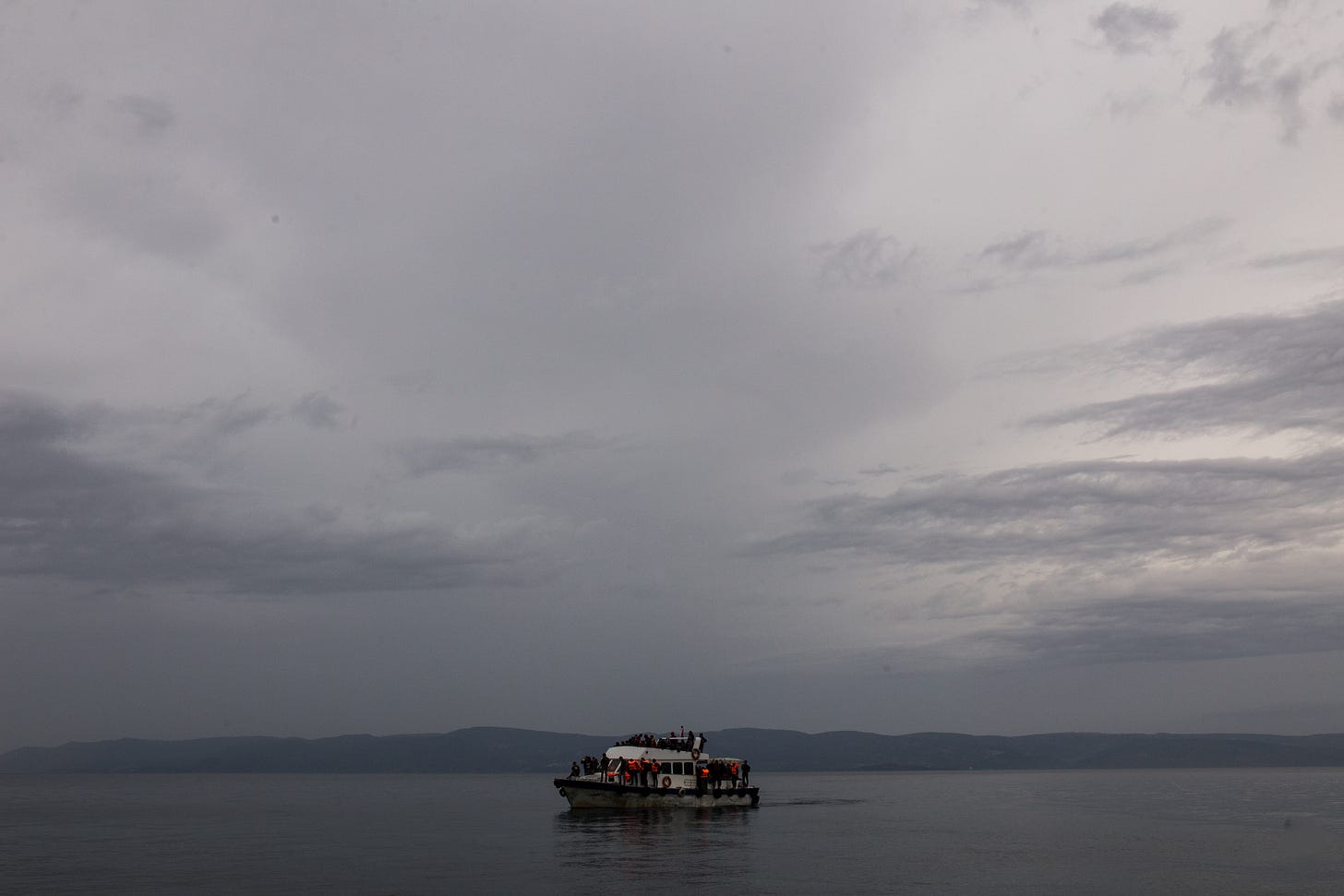

Just weeks before Vance’s speech in Munich, on the morning of Dec. 20, the death toll in the Mediterranean continued unabated. A Greek coast guard vessel spotted a speedboat nearing a beach on the island of Rhodes. The boat had left Turkey with Afghan refugees in tow, and rather than attempt to reach Greece’s much closer Aegean islands, it had set off for Rhodes, an increasingly common arrival point for refugees and migrants. The smugglers in charge of delivering the Afghans to European shores likely hoped to avoid the Greek coast guard vessels that have ramped up patrols of the traditional migration routes in the Aegean Sea.

Yet, the coast guard did detect the speedboat, and by its own admission, pursued it in a high-speed chase. The vessels collided, the purported smuggler behind the wheel lost control, and passengers began to tumble overboard. Several were injured, and at least nine people died. According to the Greek daily I Efimerida ton Syntakton, the boat’s propeller beheaded a four-year-old girl and severed one man’s leg. Two Turkish citizens were arrested and accused of smuggling. Meanwhile, Greek authorities quickly transferred most of the survivors to Leros, an island that hosts one of the prison-like refugee camps the government calls Closed Access Control Centers.

Details of the deadly incident were still trickling out in the days following the crash, but Greek officials already knew whom to blame. Smugglers had “sacrificed the lives” of the victims in pursuit of “illegal profit,” insisted Greek shipping minister Christos Stylianides in a statement the next day. The “major problem of illegal immigration,” the minister added, “exceeds the limits of the European Union’s endurance.”

It was a familiar line of deflection, one that Greek and other European officials have used for years, and one that has long been common in the United States as well: smugglers are solely to blame for any injury or hardship refugees and migrants endure. During a press conference in Vienna last September, right-wing Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis complained that “wretched smugglers” were the ones deciding “who enters the European Union.” Less common is anything that resembles serious consideration of whether increased border patrols and a tunnel-vision focus on enforcement through deterrence have, in fact, helped push desperate people into the arms of smuggling outfits.

On the borders of the U.S. and the EU, deterrence is the de facto law of the land. The logic goes like this: If border authorities can ratchet up the risks, and make the journey too dangerous to consider, then fewer refugees and migrants will attempt to reach the continent. In Europe, extrajudicial returns known as pushbacks — when authorities capture and summarily expel people who have crossed the border — often violate both European and international law, but they nonetheless make up a crucial, if rarely acknowledged, part of the EU’s deterrence strategy. More times than not, pushbacks involve gruesome violence, and in effect, they strip refugees and migrants of their right to request asylum.

Pushbacks have been taking place for years, but EU countries carried out more than 120,000 in 2024 alone, according to “Pushed, Beaten, Left to Die,” a report that nine nonprofit watchdogs recently compiled. People fleeing both war and economic catastrophes turned up on EU borders, then found themselves forced back to the country from which they crossed. Official denials that pushbacks take place at all are common. Bulgaria, for instance, has insisted the refugees and migrants returned by their own volition, a claim the report said was untrue in “the vast majority” of documented cases.

In 2023, Bulgaria carried out more than 175,000 extrajudicial expulsions. In April that year, I traveled to Harmanli, a Bulgarian town that is home to one of the country’s refugee camps. Harmanli is a scatter of rundown, communist-era apartment towers, weathered brick homes, and corner-store casinos advertising roulette and video slot machines. Still, the interior of the camp, residents told me, was far worse: people were crowded into tight, bed-bug infested rooms, the food was hardly edible, and they used communal bathrooms with broken, often overflowing toilets. I asked Ahmed, a 16-year-old Syrian Kurd, about his experience on the border, and he told me Bulgarian police pushed his group back twice before he and the others successfully crossed. “It doesn’t matter whether you surrender,” he explained. “The police hit you … and they hit to break bones.”

But the violence isn’t just happening on the Bulgarian-Turkish border. Displaced people trying to enter Hungary from Serbia, too, met brutal beatings and threats. For thousands who have crossed from Serbia or Bosnia to Croatia in recent years, entering the EU meant being greeted with police batons and threats. Those crossing the Aegean Sea or the land border from Turkey to Greece, likewise, routinely speak of violence at the hands of border authorities and Frontex, the EU’s external border agency. Greek border officers and coast guardsmen, they say, often beat and rob them of their phones and travel supplies.

In late 2022, I met Ali Muhammadi, a 22-year-old Afghan refugee, in Athens. By his own tally, he had tried to cross the Greek-Turkish land border at least 15 times before he finally made it. Border guards confiscated the phones of everyone in his group each time, and during a handful of crossings, they forced the refugees to strip and walk back across the border in the cold. “In our minds, they were belittling us and punishing us in order to [tell us] to not come again,” he told me. “Of course, it doesn’t work.”

Ali was right. Deterrence hasn’t stopped people from coming — more than 62,000 people reached Greece in 2024, a 27% increase from the previous year — but it does make the journey far more dangerous.

As the U.S. rushes forward with its far-reaching assault on migration, officials are making similarly cynical calculations halfway across the world. After Syrian rebels toppled Bashar al-Assad in early December, EU countries lined up at a breakneck pace to discuss the possibility of sending refugees back to the war-torn country. Some immediately froze Syrian asylum applications, and Austria announced a program to launch “deportations and repatriations.” Grimmer still, deporting Syrians wasn’t a new discussion in the EU — even before Assad’s collapse, several European countries had long floated the idea of returning Syrians to so-called safe zones in their homeland. Now that the Syrian regime’s prisons have been opened, now that the prisoners have been freed, the world has an even more detailed sense of what much of Europe was willing to condemn Syrians to.

Back in Greece, the deaths off Rhodes in December didn’t attract much attention beyond joining what has become an endless stream of headlines about fatal shipwrecks and smugglers. After news of the Dec. 20 coast guard chase broke, the Greek daily Kathimerini pointed out that smugglers are increasingly using speedboats, a development that “poses new risks.” On top of speedboats, Greek headlines routinely speak of shootouts, boat-ramming incidents, and would-be asylum seekers turning up on islands that are further from the Turkish coast and on uninhabited islets.

Meanwhile, the bodies were already piling up before Dec. 20 — in November, a pair of shipwrecks off Samos killed at least 12 people, including children — and they have continued to pile up on the edge of Europe ever since. On Christmas Eve, a corpse washed up on Gavdos, Greece’s southernmost island, and authorities said they believed it was the eighth confirmed victim of one such shipwreck earlier in December, adding that around 30 people remained missing. Shortly before the clock struck midnight on New Year’s Eve, more than 20 people perished when a boat sank near Italy’s Lampedusa, and a couple days later, 27 more died when two Europe-bound boats sank off the coast of Tunisia.

In its 2024 annual report, the United Nations refugee agency found that forced displacement across the world hit a record high of 120 million in 2023 — it was the 12th year in a row that the number had grown. Of the more than 208,000 displaced people who reached Europe last year, half had fled Syria or Afghanistan, both of which largely remain in ruins. It’s impossible to say for certain how long it will take for either of those countries to become safe enough for all their citizens.

What is certain, though, is that refugees and migrants from all over the world will continue to face hostility and violence on the borders of Europe and the United States. More certain yet is that no matter how many new restrictions European governments or the Trump administration introduce, no matter how many deportation schemes either drum up, and no matter how much violence they inflict on the displaced, people will continue to risk these journeys. People fleeing war, persecution, ecological and economic devastation know, too, that deterrence policies could doom them to drowning in the Mediterranean or dying of dehydration in the deserts of the American southwest, but what other choice do they have?

Read more: Read More

Read more: Read More