This is a modified excerpt from We Just Want a Chance to Stay: Stories from Guatemala and the Borderlands on Climate and the Right to Stay, a report just published by Climate Refugees, an organization that brings attention to and takes action to help people displaced by climate change. Amali Tower is the executive director of Climate Refugees and a longtime friend of The Border Chronicle. Check out this podcast we did Amali in June! We are honored to feature her on-the-ground writing, especially important as the United Nations Climate Summit (COP30) in the Brazilian Amazon has started and will continue until November 21.

We Just Want the Chance to Stay: Stories from Guatemala and the Borderlands on Climate and Belonging

“That, to me, is what climate adaptation should look like: It’s small cooperatives, youth projects, local entrepreneurship: investments that don’t just protect against storms but nurture belonging.”

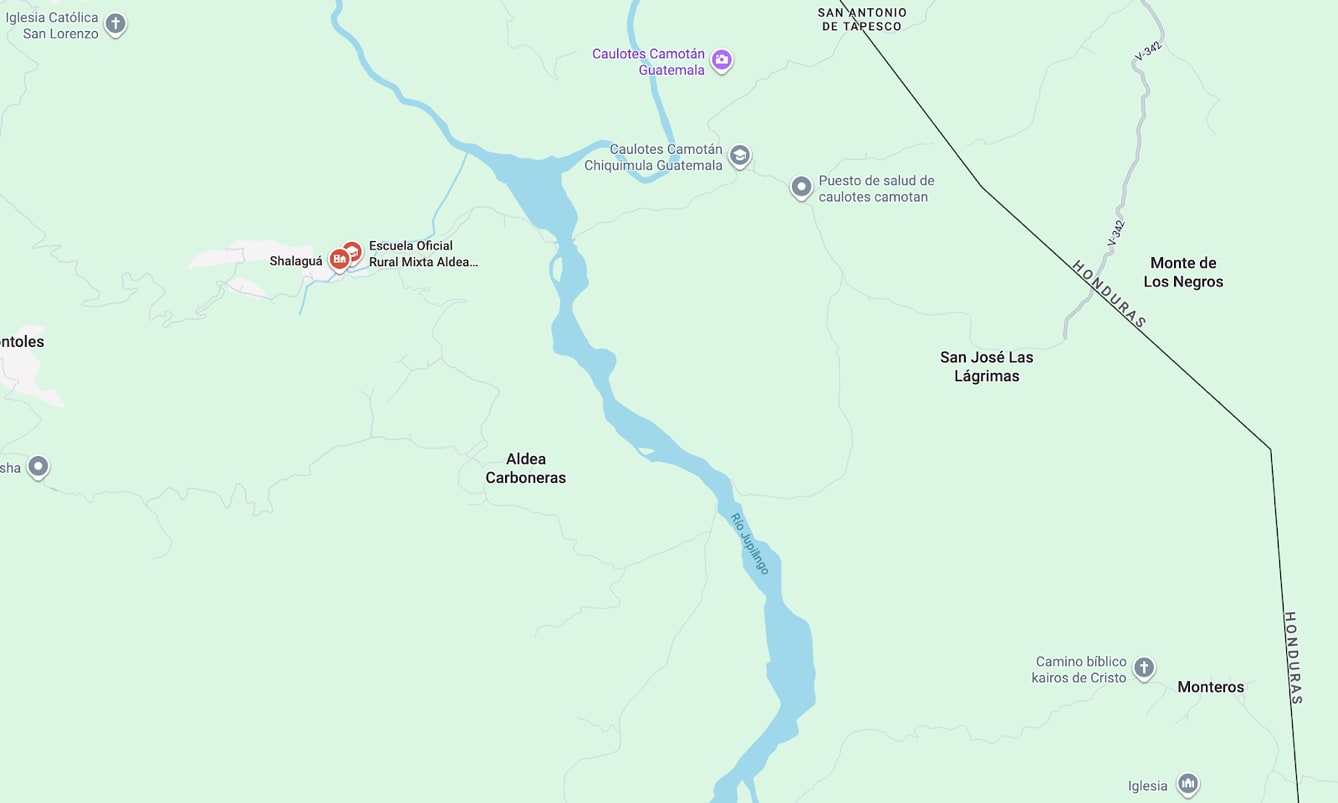

Shalaguá, Chiquimula, Guatemala

“We just want a chance to stay in our country.”

That was the first thing they told me, seated on the banks of a waterway that had slowed to a trickle. We were in Shalaguá, a village in Guatemala’s Dry Corridor region, just 12 miles from the Honduras border. Its name means “a lot of water,” fitting for a place fed by many streams. But names can become memories.

“There should be water here by now,” one of them said, pointing to the parched earth behind us. “But you see … there isn’t.”

I did see. Where a steady flow of water should have been, there was now little more than a thin ribbon of water and scattered stones. That water also flows into the Jupilingo River, the main artery for this region. But the rains had been late for weeks, a sign of shifting rainfall patterns, and another reminder of the unpredictability climate change brings.

The group sitting with me was small, Maya who were a cross section of the community: two farmers, two self-employed business owners, one aspiring lawyer. They carried themselves with the weariness of people who work harder each year to secure less.

“I have three jobs,” one man explained. “My father was a farmer, and his father before him.”

I asked if he still farmed. He smiled faintly and shrugged. “Sí … but it’s not like my father’s time now.” He gestured toward the hills. The rivers run lower than in years past, he said, and deforestation has stripped the land of its natural resilience.

“There’s no water because we can’t rely on the rain,” another added. “And then there’s too much,” someone else said as they all nodded in unison.

I had asked if climate change was a factor, and just as my words were being translated, their heads nodded up and down in unison with a declarative “Sí!”

I knew from my earlier consultations with ASORECH, a local NGO, that their words echoed a wider truth. Water, especially for cultivation, is the greatest need in this region. Without it, farming becomes a gamble few can win.

María, a widow, sat quietly in the middle of the circle. When she spoke, her voice was steady but tired. Her husband, a farmer, had passed away, leaving her with grief and no income. She had thought about leaving for the United States, but visas are impossible to obtain, and the thought of abandoning her home weighed heavier than hunger. “I don’t want to leave my home,” she told me.

With ASORECH’s help, María started a small café. That day, she invited our small group for lunch: an open-air kitchen shaded by a massive tree, a few plastic tables scattered beneath it, a hammock stretched lazily nearby. The food was simple and nourishing, and offered with pride. When I told her how much I enjoyed the meal, her whole face lit up.

ASORECH’s irrigation project had begun to change lives here. One farmer, weary but determined, told me about the beans and maize he could now grow. Then, breaking into a smile, he added, “I have even established aquaculture for the first time.”

Félix, another villager, listed his jobs—barber, mechanic, butcher. “We all have several jobs,” he said as the other farmers nodded. “We have to … to survive.”

In Shalaguá, everyone is a farmer. The land binds them, even as it betrays them. Whether they can still farm in the future is the question that shadows every conversation, every meal, every hope for staying.

Militarism, Border Security, and Climate Finance

But wanting to stay is not the same as being able to stay. Remaining on ancestral land in the age of droughts, floods, fires, and extractive industries requires more than resilience; it requires resources. Real money. Real protection. Real political will.

Yet rich countries collectively spend trillions on defense and hundreds of billions more on border enforcement. By contrast, public international climate finance—funds designated for loss, damage, and adaptation—remains tiny. The mismatch is stark: militarized responses and border spending have ballooned while the funds that help vulnerable countries adapt to the climate crisis or recover from increasing climate effects are still measured only in the hundreds of millions.

How much is spent on border security and immigration enforcement?

-

United States (border enforcement): With a goal to deport 1 million immigrants each year, new funding legislation now allocates more than $170 billion over four years for border and immigration enforcement, which the Brennan Center for Justice says has created the “deportation industrial complex.” The Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency will receive the biggest share of the new budget, totaling $75 billion over four years or $18.7 billion annually—nearly triple ICE’s budget for FY 2024. Factoring in the $10 billion that ICE had already been granted, ICE now has a budget of $28.7 billion this year to arrest, detain, and deport immigrants.

-

According to the Brennan Center for Justice, the law substantially increases funds for deportations but does nothing to shore up the immigration and asylum system, which has a backlog of millions of cases.

-

According to the Transnational Institute’s (TNI) report Global Climate Wall, from 2013 to 2018, the United States spent roughly 11 times more on border/security enforcement than on international climate finance.

-

Other rich countries: TNI has found that the seven biggest emitters—the United States, Canada, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, France, and Australia—are collectively spending 2.3 times more on arming their borders than on providing climate finance to help countries at risk adapt to the climate crisis.

-

Individually, these countries are spending two to 15 times more on militarizing their borders than on climate finance.

U.S.—a sharp contrast (military and border vs. climate funding)

-

U.S. military (2024): $997 billion

-

U.S. international climate finance: Biden administration reporting estimated $9.5 billion allocated in 2023, plus a $3 billion pledge to the Green Climate Fund over multiple years (U.S. Department of State).

-

Loss and damage (U.S. contribution): Under the Biden administration, the U.S. pledged only $17.6 million to the loss and damage start-up phase in 2023. An administration change, and political shifts in the Trump administration, have affected ongoing engagement with the fund and with international climate finance in general. Meanwhile, the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage’s pooled pledges remain under $1 billion—tiny next to U.S. defense or border budgets.

As the UN climate talks—COP30—convene in Belém, Brazil, they offer a pivotal moment for rich, polluting nations to step up and deliver the long-overdue climate finance that poor countries, migrants, refugees, and displaced populations desperately need. The meeting is not simply about emissions targets but about ensuring that developed countries and polluting industries commit to a new goal of providing over $1 trillion annually in climate finance that developing countries need by 2035. This COP30 will also pilot a new Global Ethical Stocktake—shifting the conversation to the moral, cultural, and ethical dimensions of climate change, just as a new Guardian investigation reveals that thousands of fossil fuel lobbyists with unprecedented access to COP processes have blocked progress on climate action. The message for COP30 in Belém is clear: the money that fuels the climate crisis and funds the border industrial complex must instead be channeled to climate adaptation and loss and damage finance.

Agua Prieta, Sonora, Mexico

One of the answers to the climate dilemma might be in the border town of Agua Prieta in Mexico. The first time I sat at Café Justo, I was struck by how ordinary it felt. The clinking of cups, the aroma of freshly roasted coffee, laughter bubbling up from the next table. But beneath the hum of a café, something extraordinary was happening.

The farmers who built this cooperative had not only grown coffee; they had grown a future. One man leaned forward as he told me, “I didn’t want my children to be what I am. I wanted them to be professionals. Not in the United States. Here. In our own country.”

I remember looking around the table, catching the nods of others, the quiet weight of agreement. It wasn’t anger in his voice. It was longing. A simple dream: that the next generation could thrive without leaving everything behind.

And I thought, my God, isn’t that what we all want? Whether or not we have children of our own, we hope that those who come after us will live with dignity, security, and possibility. For me, that hope is the reason I do this work.

My thoughts went back to months earlier, when I had been on the border of Guatemala and Honduras, and had met that small group of men and women gathered under the shade of a tree. The air was thick with heat, the sound of motorbikes and roosters competing in the background. One young woman, a student of international law, spoke softly but firmly: “We just want a chance to stay.”

Her words hung in the air. Everyone nodded: farmers, entrepreneurs, parents working two or three jobs. Despite their different paths, they all said the same thing: we want to stay.

That refrain has followed me across borders, across years of work.

And yet U.S. policy often answers with the opposite. Trade deals like the former NAFTA and CAFTA promised prosperity but left small farmers devastated and displaced, their markets undercut by cheap imports. Climate change compounds those losses; years of drought leave fields barren while floods sweep away entire harvests. Multiple droughts since 2014 have left farmers with consecutive years of crop losses of at least 70 percent, while periods of intensive rainfall have also damaged crops. When families cannot feed themselves, migration is no longer a choice; it’s survival.

But what I witnessed at Café Justo tells another story. Twenty years ago, a group of farmers secured a $20,000 loan to launch their cooperative. It was not a grand international plan; it was a simple act of faith: that by working together, they could build a life strong enough to keep families rooted.

That cooperative recently celebrated its 20th anniversary. And when I took that first sip of their coffee, rich and strong, I thought about the artistry behind it, the hands that planted, harvested, roasted, and shipped it, all with the same goal: a dignified future at home.

That, to me, is what climate adaptation should look like. It’s not just seawalls and solar panels. It’s communities creating the conditions to stay. It’s small cooperatives, youth projects, local entrepreneurship: investments that don’t just protect against storms but nurture belonging.

Yet we see billions spent instead on border walls, surveillance towers, and detention centers—militarized solutions that paint migration as a threat rather than what it so often is: an act of sacrifice and care.

Over 25 years of talking with people on the move, I’ve never once met someone leaving joyfully. Every story I’ve heard is threaded with sacrifice: parents crossing for their children, sons and daughters crossing for their families. The narrative that migrants are dangerous or opportunistic collapses when you sit and listen. What emerges instead is love, responsibility, and unimaginable courage.

And it leaves me wondering: What if our policies honored that sacrifice? What if climate adaptation funding centered the right to stay, investing in the same kinds of small, creative, community-rooted solutions I’ve seen in Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico?

Because when a farmer tells you, “I wanted my children to be professionals here, in our own country,” there is no complexity to unravel, no need for jargon or geopolitical analysis. It is a human truth, one every person can understand.

We all want a chance to stay.

And climate justice, at its core, must begin there.

Read more: Read More

Read more: Read More