When Russ McSpadden was a child growing up in a military family stationed in Germany, his father brought him a piece of the Berlin Wall. At the time McSpadden didn’t understand the political meaning of the piece of concrete, but he could see in the adults around him that the wall’s destruction had come with feelings of joy and liberation.

Now a resident of southern Arizona, McSpadden lives near another wall—the U.S.-Mexico border wall. And in his role as Southwest Conservation Advocate for the nonprofit Center for Biological Diversity, McSpadden has fought its construction for years. Environmental waivers passed by Congress in the aftermath of 9/11 mean that few opportunities for legal challenges are on the table; instead, anti-border-wall advocacy is a work of witnessing and documenting what is being lost. As other means fell short to describe his experiences, McSpadden turned to poetry. His first book, Borderlings, published by the Tucson-based Artspeak Press, was released in October.

Borderlings chronicles McSpadden’s decade-long immersion in the destruction wrought by border wall construction. The book is interwoven with vocabulary drawn from biology and militarization, along with phrases from his young son. It evokes settings that are unmistakably drawn from the Sonoran Desert and Madrean Sky Islands and mixes them with others that are much more dreamlike. Turning repeatedly to the idea of “ecosystems of the missing,” it captures a grief for the many forms of loss enacted by militarization. Such grief is seated deeply in many people in the borderlands. “We pay for borders with everything / all around them is every beautiful thing,” McSpadden writes.

What was the process of writing Borderlings?

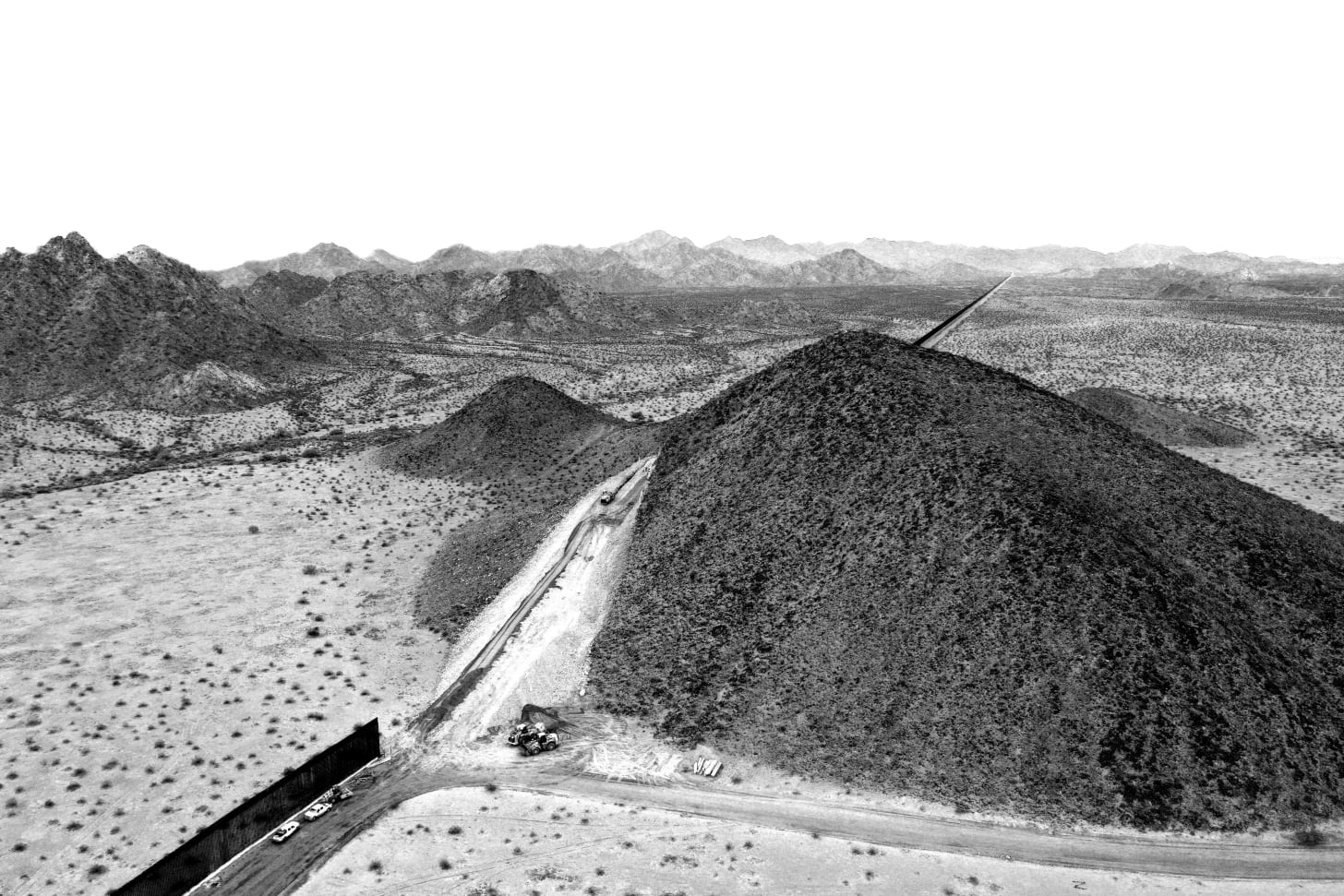

It’s been in the works since 2019 without me quite knowing it. I was working a lot at the border. Border wall construction was going on everywhere, including across public lands and wildlife refuges.

Where I work, we use law to defeat bad projects on public lands. But because of the waivers, that doesn’t exist [for the border wall]. We have no real foothold—we can’t sue over the Endangered Species Act or the Clean Water Act. None of that. So I was watching, for instance, at the San Bernardino National Wildlife Refuge, that they were pumping all of this water from the nearby springs. The springs had been a water source for people and wildlife for millennia. And they destroyed them. But we couldn’t fight it.

All of it was so brutal and shitty. As soon as I saw there was a word, Mauerkrankheit, or “wall sickness” [coined by a German physician to describe the emotional and physical impacts of living in the shadow of the Berlin Wall], I thought, I get it. Because I would come back from these trips really nauseous, and it would be embedded in my dreams, this feeling of being trapped. The border would really come up. And I didn’t really have any other way to access some of that except for writing—journaling, notebook work.

Then, Johanna Skibsrud, a professor at the University of Arizona, looked through some of the journals and got pretty excited about it, and there was a grant to work with Logan Phillips [a poet and the publisher of Artspeak Press]. There was no deliverable. We would just hang out and check wildlife cameras together. We started working together and thinking about a more formal writing project.

How did you get interested in poetry?

Since I was a kid, I always liked to write poetry. In middle school I was introduced to Emily Dickinson, and I was in love with the mystery, with trying to decipher what was going on in the strange, mystical language she was using. It was life changing.

Were there poets that particularly influenced this book?

The poets I was reading around the creation of the book were Susan Briante, especially the book Defacing the Monument; Whereas, by Layli Long Soldier; Look, by Solmaz Sharif; Ghost Of, by Diana Khoi Nguyen, Sonoran Strange, by Logan Phillips; and Tribute Horse, by Brandon Som. Those books all helped me see a path of language for moving through liminality and grief and monolithic forces. Also Disabled Ecologies, by Sunaura Taylor.

Your book has a unique way of bringing bureaucratic and militarized language and scientific language into the poems.

In some ways I’m just trying to dissect my heart and understand what I was experiencing—but then also dissect militarization and what it’s like to stand in front of it. The hard part was being in some of the most beautiful places and having wildlife cameras all over the border in the Sky Islands, and seeing jaguar and bears and lions and all of these creatures and knowing what the impacts will be.

There’s this whole ecology of violence at the border that’s there for migrants, there for nationalism, but that has all these side effects on jaguars and springs and spring snails and moths.

Some people might say that snails and moths and even jaguars aren’t as important to be worried about when there is such a human rights crisis at the border. How do you see the importance of conservation work at the border?

The wall’s sole purpose is to harm humans and harm people considered outsiders. It’s not the intent of the wall to harm jaguars or other wildlife—it’s an ancillary symptom of the project. But I think the protection of the ecology of the borderlands is critical work. It’s not separate from the human rights issues. They are two different things, but, for instance, there are border communities that are affected by the waivers of local, state, and federal environmental laws. Those waivers make the border a lawless zone for communities that live there—laws that are bedrock laws for every other American.

With the jaguar, it’s this charismatic megafauna. But one reason we sought to get its habitat listed as critical under the Endangered Species Act is that it’s a wide-ranging species. So it’s about 700,000 acres of critical habitat. And that creates a huge umbrella of protection for a lot of other species that people are less revved up about, like spring snails.

I’ve worked with two tribes and two schools to name the last four jaguars, and it’s amazing to see the border communities see the jaguars as a positive symbol. No one’s reintroducing it. It’s returning on its own, reestablishing territory, and it’s a sign that there’s something healthy in the mountains where they live, and there’s a sense of pride in that.

There are a lot of insects in the book.

I only realized this toward the end, because I was reading it again. There are insects in half the poems, I realized. My kid is an insect nut, and I think he’s infected me.

[In one poem] I talk about counting these solitary bees at the San Bernardino Wildlife Refuge. That valley has the highest bee diversity on the planet, at least so far known. There’s something about a xeric environment that can lead to intense speciation—they all find their little niches, different flowers, different pollen, the different springs.

I’m really captivated and in love with borders—not militarized or nationalist borders, but borders like the kind in the Sky Islands, where there are species that will only grow about eight feet high on a cliff that’s north facing, with a certain amount of precipitation and overgrowth. Or how if you head north from Tucson towards Benson, you lose saguaros for the rest of the state, because of elevation and temperature. There are all these restrictions, but not in the sense of an alien restriction from outside, just in natural ways. I’ll see a plant outside of its border, and I’m like, Hey, good job, you found your way. That’s where speciation happens. That’s where the abundance of life happens, when things are moving around and finding new niches.

Do you think the U.S.-Mexico wall could go the way of the Berlin Wall?

I asked my dad a similar question not long ago: Did you know the wall was going to come down? He said, No one knew that wall was going to come down. I was like, Good. That’s kind of inspiring. It just sort of happened. There was some tipping point that I don’t think anyone quite knew. Maybe we’re in the next run of that.

I really love history, and I feel pessimistic in the short term but optimistic in the long term because of it. I think we have to show these things [happening at the border] because maybe they’ll become unsavory at some point. And there’ll be a history of people resisting it, a record of the damage and what was there before and what could be restored. Human rights, wild places, all of those things.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. Borderlings is available from Artspeak Press.

Read more: Read More

Read more: Read More