The Rio Grande is bringing water into El Paso only from early June through August this year, a short river season that will leave El Paso Water more reliant on pumping the region’s aquifers to meet the city’s demand for water.

Still, the river’s water flows are welcome for the summer because it’s the time of year when El Pasoans consume the largest amount of water – as much as 160 million gallons daily, about 50 million gallons more than the annual average daily consumption, according to El Paso Water’s financial reports.

“It is a much shorter period than what we’re used to. Usually, we get water from the river from March through October, just like we did last year,” said Gilbert Trejo, El Paso Water’s vice president of engineering, operations and technical services. “But, the most important thing is we have the river water during the hottest time of the year, when El Pasoans are using the most amount of water.”

El Paso Water will draw as much as 100 millions gallons of water from the river every day and treat it to drinkable standards at the utility’s two river water treatment plants: the 82-year-old Robertson-Umbenhauer plant in the Chihuahuita neighborhood in South El Paso and at the newer Jonathan Rogers Water Treatment Plant in the Lower Valley.

The amount of water that flows through the Rio Grande into El Paso during spring and summertime depends on how much snow accumulates over winter in the mountains of southern Colorado and northern New Mexico.

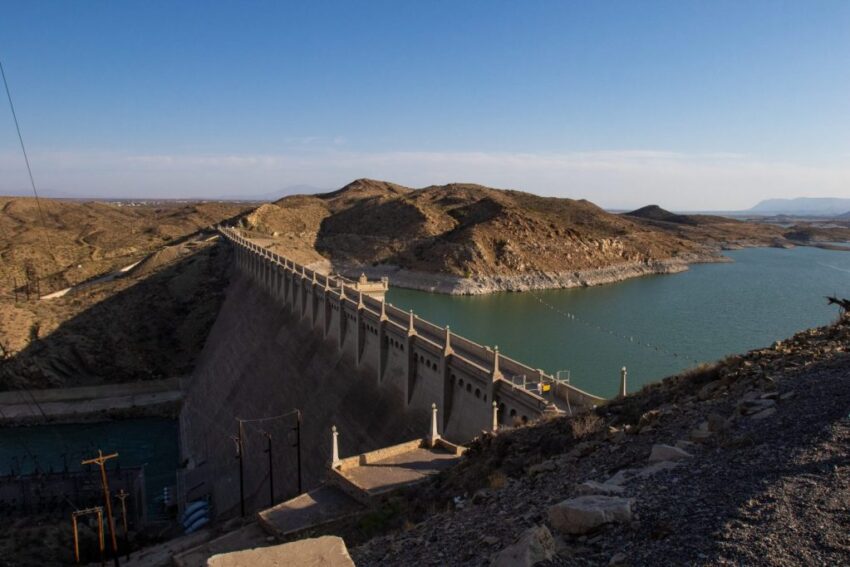

Once snow melts after winter in those mountains at the head of the Rio Grande watershed, it flows south through New Mexico, where cities such as Albuquerque draw and use some of the water, treat it and re-insert it into the river before it reaches Elephant Butte, where the water is then released to El Paso.

The amount of water El Paso gets from the Rio Grande varies widely year to year.

In 2020, water from the Rio Grande supplied 38% of the city’s water supply, but in 2021 and 2022, the river supplied just 14% and 17%, respectively. In 2023, river water provided 31%, while last year, river water was relatively plentiful, when it supplied 44% of the city’s water supply.

Managing the Rio Grande’s variations

That annual fluctuation, which is difficult – if not impossible – for El Paso’s water planners to predict more than a year out, is why El Paso Water has spent heavily to develop new ways to produce drinkable water for the city. That’s also why El Pasoans’ water bills have escalated significantly over the last several years. Over the last three years, average household water bills have increased by more than $18 per month.

City-owned El Paso Water has been using some of the additional cash generated by the rate increases it has enacted in recent years to expand the utility’s unique desalination plant near the El Paso airport and to start building a new treatment plant.

The Kay Bailey Hutchison Desalination plant takes salty groundwater from the Hueco Bolson aquifer and produces as much as 27.5 million gallons of drinking water daily. In the coming years, the utility will add on to it so the plant can pump out as much 33 million gallons every day.

Meanwhile, El Paso Water broke ground earlier this year on the Pure Water Center, an advanced purification plant that will clean wastewater from the utility’s Bustamante Wastewater Treatment Plant in the Lower Valley to drinkable standards and pump as much as 10 million gallons of water daily into the city’s drinking water system within the next few years.

The Pure Water Center, expected to cost around $300 million to develop, will be novel and cutting-edge for the water industry and will include five treatment processes. The idea is to drought-proof El Paso, meaning the utility could meet the city’s demand for water as normal even if no water flows into the Rio Grande, El Paso Water’s CEO John Balliew has said.

Water experts have said El Paso’s advanced purification plant will serve as a model for other arid cities that will likely implement similar water recycling technology in the near future.

“We call it ‘pure.’ We talk about the quality of the water, not the history,” Scott Reinert, water resources manager for El Paso Water, said in an interview last month on the Texas Standard radio show.

Still a reliance on the river

Despite the relatively short amount of time the river will be delivering water into El Paso this year, it plays an important role in the city’s water system for now.

It’s cheaper and simpler for El Paso Water to pump fresh groundwater from the two big aquifers beneath El Paso, which requires little treatment beyond adding a small amount of chlorine. An acre-foot of groundwater – enough water to cover an acre of land with a foot of water, or about 326,000 gallons – costs El Paso Water roughly $250 to produce, according to estimates from the utility.

River water, also called surface water, is the second-cheapest source of water for the utility to produce; an acre-foot costs El Paso Water something like $340.

On a recent morning at the Canal Street Water Treatment Plant tucked between a railyard and the border wall near Downtown, the plant’s superintendent, Sal Morales, led a tour of the facility to show how it draws and treats river water.

Workers at the Canal Street plant pull water from the American Canal – a cement-lined waterway that forms near Executive Center Boulevard and Paisano Drive, where a dam diverts water from the Rio Grande for irrigation and domestic use.

The utility takes solids out of the water, and then mixes it with ferrous chloride before filtering the water through a series of large basins using activated carbon, which is similar to water filter pitchers used in homes but at a much bigger scale. Throughout the process, computer monitors at each step indicate how the water becomes increasingly pure.

By comparison, El Paso Water estimates suggest it costs about $500 to produce an acre-foot of water from the Kay Bailey Hutchison plant, and it will cost a similar amount for water produced at the Pure Water Center when it’s up-and-running in a couple of years.

Importing water from Dell City, Texas, about 80 miles east of El Paso – the utility’s plan to supply water decades from now – could cost as much as $1,300 per acre-foot, according to El Paso Water.

Relying less on the river and pumping more groundwater saves the utility some money. And since the river water plants – like the Canal Street plant – won’t be operating for as long this year amid the shortened river season, that frees up some funds for El Paso Water to conduct maintenance elsewhere in its system.

Trejo said the abbreviated river water season has no budget impact on El Paso Water.

“When we get a shortened season, it does reduce operational costs at the surface water treatment plants,” he said. “That frees up money to go do maintenance at other facilities. Maintenance always needs to be done here and at all of the plants, at the pumps, the tanks, everywhere.”

However, the risk of consistently short river seasons is that El Paso Water relies too much on groundwater.

The utility doesn’t want to overpump groundwater and deplete the city’s two aquifers like it did back in the 1980s. The Mesilla Bolson holds fresh water underneath the West side, and the larger Hueco Bolson stretches beneath the eastern portion of El Paso County and holds a large amount of brackish – or slightly salty – groundwater.

Since 2020, the Hueco Bolson has annually provided as little as 36% of El Paso’s water and as much as 61%.

Cities elsewhere in the Colorado River Basin, which supplies water to seven states including Arizona and New Mexico, have seen water availability dwindle because of a variety of factors including climate change and excessive groundwater pumping.

“As Colorado River streamflow diminishes, the reliability of surface water resources has become increasingly threatened. Over the past century, the river’s flow has decreased by approximately 20%, and climate models predict further reductions of up to 30% by mid‐century due to rising temperatures and reduced snowpack in the Rocky Mountains,” read a study published last month by a team of scientists led by researchers at Arizona State University and the University of Arizona.

“This situation places immense pressure on the region’s groundwater resources. As surface water becomes less dependable, the demand for groundwater is projected to rise significantly,” the study stated.

Meanwhile, some of the suburbs of Houston, Texas have been sinking at a faster rate than anywhere else in the U.S. because of excessive groundwater pumping.

Another study published in 2022 by researchers at the University of Houston found areas west and north of downtown Houston are sinking as much as 2 centimeters per year because of excessive groundwater pumping. “… Subsidence may be causing fault movement in this area. If current ground pumping trends continue, faults in Katy and The Woodlands will likely become reactivated and/or increase in activity over time.”

In El Paso, Trejo said the groundwater table is generally 200 to 300 feet below the surface, so El Paso has avoided the sinking effect – called subsidence – that other cities are facing.

“Although we are in the Southwest, our water situation is very different from what Arizona and Southern California, Nevada, anyone tied to the Colorado River and what they’re facing with Lake Mead and with allocation … We are very different from that situation, so that is not us,” Trejo said, also mentioning the sinking issue in Houston.

“We simply just do not have those groundwater or soil subsidence issues in El Paso,” he said.

After the river water arrived in El Paso earlier this month, Trejo acknowledged El Paso Water customers may notice a slight difference in the flavor or odor of water flowing from household taps. That’s because the treated river water mixes with desalinated and fresh groundwater in the utility’s system.

“They may see some changes in the taste and the odor for the next several weeks as the pipes and tanks, frankly, acclimate to this mixture of water,” he said. “But we want to assure our customers it’s absolutely safe to drink.”

The post El Paso is getting less water from the Rio Grande this year. What does that mean for the city’s water supply? appeared first on El Paso Matters.

Read: Read More

Read: Read More